A Criticism of Wittgenstein’s Private Language Argument

Wittgenstein’s Private Language Argument appears in the Philosophical Investigations from around p.243 to p.315. For some good summaries/accounts on the argument or the Philosophical Investigations itself, scroll to the very bottom of this article. The so called private language argument is invoked a lot of discussions about language, particularly in trying to prove in some sense that all conscious thought (or even all of consciousness) reduces to language.

The gist of the private language argument is attempting to show how all the ways language could be private do not actually work. Roughly speaking, what is meant by ‘private language’ is a mode of thought that is not public so it is not able to be expressed through public language. So what Wittgenstein is trying to show, at least on the common interpretation, is that language has to be public with meanings determined by human agreement/convention, and that all our thinking occurs through this public language.

Problems with the Private Language Argument

Wittgenstein makes a series of wrong/naïve assumptions throughout his argument though to be fair, this seems common with all the logical positivists. I will cover two broad ways he is making these mistakes.

Private Language is assumed an Analog to Public/Natural Languages (like English). But Why?

To begin with, we are to imagine ‘private language’ as an analog to public language, with the goal being to show how that idea doesn’t work. That should already be a red flag. This view also seems to presuppose the entire process of language and thought is fully transparent to itself in a way that everything about the mind can be put into language. But that is putting the cart ahead of the horse… The fact that we are still stuck on a fairly meaningless word, consciousness, should be quite good evidence that whatever is going on in the full process, language does not easily account for it. There is no necessity that consciousness needs to be intelligible to language.

If a concept of ‘private language’ doesn’t work, then the problem is more likely with the concept of private language itself. There is not really any meaningful reason to even call it ‘private language’. Non-linguistic thinking or pre-linguistic thinking are more appropriate. And it seems likely that non-linguistic thinking would be continuous with unconscious processes and would itself possibly be at the ‘edge’ of conscious awareness. There is no reason non-linguistic thinking would be an analog to linguistic thinking.

Why does Wittgenstein insist that private/subjective thoughts/sensations would need to take the form of a private ‘language’? The answer is because it’s part of his (flawed) logical positivist agenda assuming Logical Empiricism. Specifically, he assumes there must be some type of criteria of correctness for a word to be meaningful. This is inherited from the logical positivist agendas which ultimately didn’t succeed in any of their projects. So for instance the claim that:

‘The signs in language can only function when there is a possibility of judging the correctness of their use, “so the use of [a] word stands in need of a justification which everybody understands” (PI 261, source)

In contradiction to this point, in the second chapter of The Language Instinct, Steven Pinker goes over countless studies of how children learn language by an innate understanding or internal set of rules that they are not (do not need to be) exposed to, prior to their use in language. Several cases show how children can adapt language to their own systematic rules that are different/inconsistent from their parents (who learned the language as adults); Particularly clear with Pidgin, Creole and mixed languages which historically developed from people who did not learn/create it as their first language. Cases like these suggest the child’s brain is correcting issues in the language that are in contrast to how their mind inherently processes the words and meanings. In other words, they are fitting the public language into their own innate rules; that there is some sort of internal grammar/rules prior to ‘learning’ a ‘natural language,’ and that all natural languages need to conform to some innate rules to even work for us (another of Pinker’s points).

This idea of innate rules to language or a universal underlying structure runs counter to logical empiricism and empiricism generally, and instead lends evidence to transcendental idealism.

Getting back to topic, in short, there is no reason private/subjective thoughts or sensations need to be in a language-form at all. In discussing this, I was recently asked, “Daniel do you know a particular smell – any scent – without language? Similarly with taste – do you know any taste that is not languaged [sic]?”

The answer is, I do but I can’t tell you about it! Likely so do you. Have you ever tasted something, something distinct, but not known what it was (the word), and therefore not been able to identify it? Same with sound, if you have heard something distinct but not been able to identify it with a known object or word. A consistent sound/taste can happen over multiple instances and I don’t need a word or any type of ostensive sign for it because I can remember the sensation itself, directly, without describing it in words. Yes I *can* name it but I don’t have to and naming it doesn’t change anything except for language. So I don’t *need* any means to verify the similarities of the instances. That is part of a different (and flawed) agenda of Logical Empiricism with no reason to assume this is part of the actual conscious process.

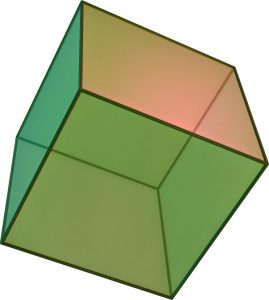

To be clear, just because something can be put into words does not mean it originates as words (or through a linguistic process). Dictionary-type meanings like “a cube is a three-dimensional solid object bounded by six square faces” (Wikipedia) are Public. But the meaning itself that I am trying to express using publically available tools (words), seems private. What I see here is private:

The visual understanding is not natively in word-form so it is incorrect to say that I cannot understand what a cube is without language. We should turn that around and say a cube has no meaning (or a very abstracted and empty meaning) without the mental processes of visualization which is part of consciousness. Visualization is not vision itself but is used in understanding vision. It is not language but it is used in meanings that we can communicate through language.

Ostensive Definitions in a Private Language

Part of the private language argument is how there would need to be something like ostensive definitions in a private language (assigning a sign to a ‘this’). Again, why??

The answer is the same. This argument assumes there must be some type of criteria of correctness for a word to be meaningful. This ties into the logical empiricist assumption that, broadly speaking, everything that is known or meaningful must be verifiable on logical and scientific grounds.

This is a similar, if much more contrived, example, to the logical positivist concept of ‘sense data’ which is basically fabricating a system for no reason other than, it would need to be true IF the goals of logical positivism could have any chance of being true. But no! ‘Sense data’ is not true to the actual process of perception in consciousness, and we have good reason to believe that the mind adds quite a bit of features/structures into our perceptions that are not inherent in the ‘signals’ from the senses themselves. This is how many optical illusions can happen for example. (Again, another point for transcendental idealism over plain empiricism!)

Additionally, there is no separation between signifier and signified until public language. Why does there need to be a separation between signifier and signified in private thought? Prior to language, there is no process of matching a sign to an object. It doesn’t even make sense for non-linguistic thinking to have ostensive definitions.

The whole private ostensive definition nonsense doesn’t show anything in the first place because there is no need for separation between signifier and signified in thought, *except* for language.

In Conclusion

For the ‘private language argument’ to work, we have to assume premises of Logical Empiricism are already true; that there must be some criteria of correctness for a word to be meaningful. That all thought and sensation would need to be as an analog to natural (public) language, and therefore, that a private language would *need* ostensive definitions. That since this is impossible, private language is impossible (okay, there is a bit few more arguments than just the ostensive definitions, but you get the point!) And that, therefore private language is an oxymoron of sorts and therefore, all thought, senses, meaning, etc… is through public language.

The problem is, why would private thought need to resemble public language? If the argument is that private thought cannot be like public/natural language, then first, yes we could agree ‘private language’ is something of an oxymoron as Wittgenstein wants to show, but second, that whatever is going on is just not like natural language in every respect.

Wittgenstein’s ultimate project is to show “the meaning of a given word for a speaker of a language is determined by the pattern of its use in that speaker’s linguistic community, and a speaker uses a word incorrectly when her use is at variance with this pattern.” (source). This is basically bringing meaning out of subjectivity and into inter-subjectivity. But no, this all assumes logical empiricism is the correct account of mind, senses, experience and knowledge.

If we don’t assume logical empiricism beforehand, the correct conclusion is not that I cannot have a sensation of pain if I don’t have a word for it. Again, that is putting the cart (language) ahead of the horse. It is that, 1., the sensation of pain is distinct from the word I use to signify it. And 2., there is no need to distinguish signifier and signified in private thoughts/experiences/senses. The separation between signified and signifier seems to be a categorical separation between public/natural language and private thought.

Can we really even consider meaning as public in the first place? It seems to me, by language, either you mean language in the public sense of words, or you mean meanings in a private/subjective sense of thoughts, experiences, sensations, etc… Both can sloppily be called language because mental content *can* be put into some selected set of words, with varying degrees of expressiveness or effectiveness, but this does not mean that meaning is natively words or certainly not all forms or modes of meaning and understanding.

Learn more about the Private Language Argument

There is a fairly good and short summary here (1000 word essay summary).

And a more detailed account at the plato.stanford.edu entry.

Originally posted May 23, 2016.